By Rick Romano

Keeping America’s Latest Health Crisis Out of Our Community

Statistics point to one truth – opioid abuse has taken its unfortunate place in American culture.

The Center for Disease Control and Prevention reports overdose deaths involving prescription opioids quadrupled from 1999 to 2015, affecting183,000 people. Also, more than 1,000 people are treated daily in emergency departments for not using prescription opioids as directed.

Statistics show the issue is only getting worse, prompting President Trump on Aug. 10 to declare the opioid crisis a national emergency. That declaration, the feds say, will give states and agencies more resources to address the issue.

Taking It Seriously

The good news is Wauwatosa has not been hit nearly as hard, said Laura Conklin, the city’s health officer. The city’s Community Health Profile indicated a slight decrease of respondents who said they have taken opioids without a prescription over the course of 2013 through 2015. In addition, death certificates indicating drug abuse (including non-opioid drugs) show a range of three to seven deaths each year from 2012 through 2016.

The good news is Wauwatosa has not been hit nearly as hard, said Laura Conklin, the city’s health officer. The city’s Community Health Profile indicated a slight decrease of respondents who said they have taken opioids without a prescription over the course of 2013 through 2015. In addition, death certificates indicating drug abuse (including non-opioid drugs) show a range of three to seven deaths each year from 2012 through 2016.

Wauwatosa doesn’t take the issue for granted. Conklin is helping orchestrate the city’s prevention strategies while playing a role in regional efforts and tapping into similar efforts of neighboring communities,

“It’ a very dynamic, ever changing issue,” she said. “It’s different from other previous drug epidemics.”

Abuse starts by those overextend pain meds and, like other drug abuse, by those experimenting to seek a certain high. Over prescribing meds also plays a part.

Tosa is concentrating on prevention, but it’s not an easy target.

Unique Issue

“It’s so fragmented,” Conklin said, noting abusers who overdose and/or die can come from other communities. “When you look at heat maps, you see the problem in places like West Allis and West Milwaukee and then as you head north into more wealthy counties.”

“Police told us to put our resources into prevention because that’s where we’re going to affect the most change, she said. “We are trying to stay ahead of the curve.”

Earlier this year, Conklin and the Board of Health began seriously considering opioids as a community focal point. She garnered City Council support. The Board of Health along with its community partners, will in late September determine what issues will be addressed next. Substance abuse has been one, so Conklin assumes opioids will be part of the mix, either on its own or within the broader substance abuse category.

Alderman Bobby Pantuso, a Board of Health member, said he and his Council colleagues would like to see the plans as well as whether the state may be able to provide grants and other fiscal resources.

“It’s really not just about the opioid issue alone.” Pantuso said. “It’s about the other things that go along with the addiction. You have people breaking into pharmacies and committing other crimes in order to feed their addiction.”

Pantuso, the father of a Tosa East student, said he regularly asks whether opioids are a problem.

“It doesn’t seem to be,” he said. “The major issue there is still alcohol and marijuana.”

Tosa United’s Fred Robinson echoed that sentiment.

“For some reason, we haven’t seen that (opioid) issue in the schools,” Robinson said. “If we knew why, we would export it.”

Robinson estimates abuse is driven as much by unused prescription meds being kept around in a youth’s family medicine cabinet as well as in a grandparent’s home.

Statistic from the 2017 Wauwatosa High school Youth Risk Behavior Survey also indicates a relatively low rate of abuse compared to other risk factors. Out of 318 respondents, 11% said they have taken a prescription opioid without a doctor’s prescription. That compares to 10.7 percent of 420 who responded the same way in 2015.

Statistic from the 2017 Wauwatosa High school Youth Risk Behavior Survey also indicates a relatively low rate of abuse compared to other risk factors. Out of 318 respondents, 11% said they have taken a prescription opioid without a doctor’s prescription. That compares to 10.7 percent of 420 who responded the same way in 2015.

The Region Prepares

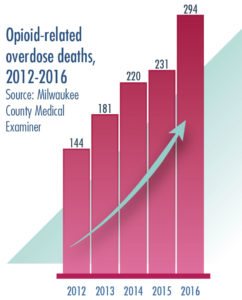

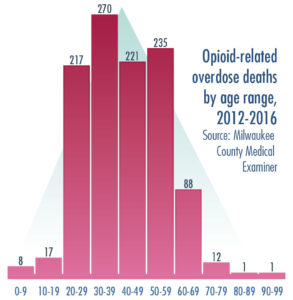

At the County level, there is COPE, Community Opioid Prevention Effort, coordinated through the Medical College of Wisconsin. A report detailing opioid-related deaths from 2012 through 2016 show a steady increase from 144 to 294. In its study of age range deaths, the largest group at 270 deaths are those between 30 and 39. The smallest groups are those in the youngest and oldest age groups.

MCW also is involved in efforts to educate and further set standards to health care professionals who prescribe opioids. About 70 health care leaders from across the state met in early 2017 at the Wisconsin Medical Society’s Madison headquarters.

Conklin is connected to that effort as well as the West Allis West Milwaukee Coalition which has been working on substance abuse issues for almost a decade. Project Manager Tammy Molter said the coalition is supported by an annual federal grant.

“We have a broad coalition of people from the police department, businesses, health organizations, religious organization and schools,” Molter said.

Officials say tackling the opioid issue will require a fiscal and time commitment.

Government Support

Prior to the President’s August declaration, the National Drug Control Policy in May requested an increase in federal funds to fight all drug abuse, including a $1.3 billion investment toward addiction and recovery programs addressing opioids. Earlier in the year, a commission on addiction was established, led by New Jersey Gov. Chris Christie.

Cooperation Needed

Closer to home, the Zilber Foundation supports MCW’s and other opioid efforts, including a $50,000 a year for three years for professional training. Executive Director Susan Lloyd said there is work to be done.

“It’s going to take a universal communitywide effort,” Lloyd said, referring to researchers. government officials, community leaders and physicians, “to come up with a shared protocol.”

For Wauwatosa, Conklin said the challenge will be to stay ahead of the curve even though a local crisis is not imminent. It’s a universal reality, she said, for any issue.

“There is always a lot more traction and passion when the effort is led by personal stories of those who have been personally affected,” she said. “Welcome to public health.”

A Life Saver

Prevention is preferred, but when that isn’t possible, there is Naloxone.

Also known by its brand name – Narcan – Naloxone is the first responder’s go-to antidote to opioid overdoses. Administered in time, it is deigned to reverse opioids most dramatic effects such as slowed or no breathing, vomiting or gurgling and bluish lips and fingernails.

“We carry it in all of our vehicles, said Tosa’s Assistant Fire Chief Jim Case. “It’s a very important part of our supplies.”

Naloxone comes in a liquid form to be administered by syringe needle, plugged into an IV or through a nasal passage (nasal application shown in photo).

The antidote was patented in 1961 and approved for opioid overdose in 1971 by Food and Drug Administration. It is on the World Health Organization’s List of Essential Medicines.

Fast Facts

What are opioids? Opioids are a class of drug either derived from or chemically similar to compounds found in opium poppies. They include legal prescription painkillers like oxycodone (OxyContin), hydrocodone (Vicodin), morphine, codeine, fentanyl, among others. The illegal heroin also is an opioid.

How do they work? These drugs bond to receptors in the body and brain, blocking pain. They also produce feelings of euphoria and relaxation – especially when misused such as taking the wrong dosage or without a prescription

Possible signs of misuse. Someone who is misusing opioids may display general mood and behavior changes as well as see drowsy and disoriented. A user may fall asleep while sitting or even standing. Slurred speech also may occur.

Disposing Unused Opioids

In response to the reality that many patients never completely use their prescribed pain medications, a Wauwatosa partnership of the police department, health department and Tosa United has sponsored a method for safely disposing them.

A mailbox-style container in the police station lobby, at 1700 N. 116th Street is for meds from Wauwatosa residents only. The collection box is available from 7 a.m. to 11 a.m. Monday through Friday and from 3 p.m. to 11 p.m. Saturday and Sunday

Accepted meds include those that are prescribed and from over-the-counter. Pills need to be disposed into a plastic d sealable type bag and liquid medications must be in the original container and similarly sealed.

Check-in is required prior to disposal to verify residency.

Items such as biohazard material needles/sharps, personal care products (shampoos, etc.).and household hazardous waste (paint, pesticides, etc.) are not accepted.

Full details are available www.wauwatosa.net and then go to Medicine Collection Program.

Drop-Off Day

Medications also can be dropped off during Tosa’s recycling day scheduled for 10 a.m. to 1 p.m. on Saturday, Sept. 9 at the parking lot behind City Hall, 7725 W. North Ave.

Wauwatosa Health Officer Laura Conklin reports the city collected a range of 160 to 240 pounds of medications per year from 2013 through 2016.