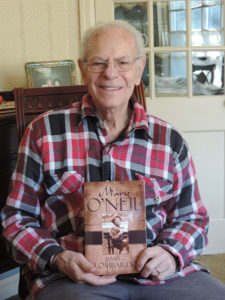

The story of an orphan, a saving grace, a parental search and an attempt to preserve dignity.

By Rick Romano

Forgetting is not an option for Jim Lombardo.

Forgetting is not an option for Jim Lombardo.

The 78-year-old Wauwatosa resident recalls his life in mostly vivid details, a skill honed through multiple interviews and his self-published autobiography. It is a life worth telling and considering because it is more than personal background; It is a window into unvarnished local history that begins to beg for answers to fresh questions.

An orphan’s life

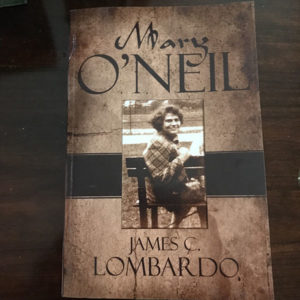

It all started in a most unseemly matter with a young woman being assaulted on Milwaukee’s East Side. As Lombardo tells it, his birth mother, Mary O’Neil, was a Wisconsin transplant from Missouri, of Irish and Native American descent and the offenders were mostly of Italian descent.

With his mother deemed by local courts as unfit by mental deficiency and therefore institutionalized in Chippewa Falls far from Milwaukee, James Lawrence O’Neil spent most of his first three and a half years orphaned at the Milwaukee County Children’s Home on county grounds north of Watertown Plank Road. There, he recalled several key memories.

“I remember sitting in a field with one of the workers and watching children around me running and playing,” he said. “I remember playing on the floor in a stainless-steel room with windows all around me.”

Saved by love

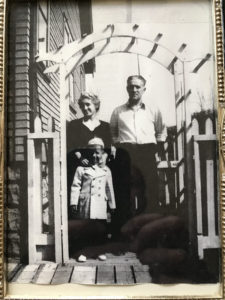

He also remembers the day Carl and Lydia Lombardo, a childless couple from Milwaukee, peered through one of those windows. On Christmas Eve of 1943, Jim went home with the Lombardo’s, first fostered and then adopted.

He also remembers the day Carl and Lydia Lombardo, a childless couple from Milwaukee, peered through one of those windows. On Christmas Eve of 1943, Jim went home with the Lombardo’s, first fostered and then adopted.

Jim had entered into a whole new phase of his life. Because he could hardly walk or talk above a baby’s vocabulary, county workers labeled him mentally challenged. But Lydia nurtured him.

“I was helped by the nature of her love,” Lombardo said. “Once I started talking, I couldn’t stop. I was a chatterbox.”

Despite the affection he felt from his loving parents, Lombardo lived with a chip on his shoulder.

“I had a rage in me,” Lombardo said. “I can’t fully explain it.”

That temper got him in more than a little trouble and in fact kept him from graduating high school. In his junior year at Boys Tech, Lombardo argued with a teacher who threw him out of the classroom where he fought with a hall monitor. The result: expulsion.

Undaunted, Lombardo years later earned his GED. But he already was developing a work ethic serving in the National Guard and working as a property appraiser. He eventually worked in facilities management for Milwaukee County.

Seeking his roots

While he was happy with his adoptive parents, he wondered about his orphanage background and birth name. He didn’t ask too many questions growing up, but after his adoptive mother died, he asked his father who helped him by sharing what he knew and showing him birth records. He eventually had enough facts to begin tracing living biological relatives through numerous phone calls and making connections , and came close to actually meeting his real mom, who had spent a number of years in a state facility for the mentally ill.

While he was happy with his adoptive parents, he wondered about his orphanage background and birth name. He didn’t ask too many questions growing up, but after his adoptive mother died, he asked his father who helped him by sharing what he knew and showing him birth records. He eventually had enough facts to begin tracing living biological relatives through numerous phone calls and making connections , and came close to actually meeting his real mom, who had spent a number of years in a state facility for the mentally ill.

His life was on full track with work, marriage, adoption (see sidebar) and marriage again. Lombardo worked at various county public works and facilities and grounds positions and eventually wound-up working at the county grounds, a close proximity to his orphan home.

In the mid-1990s, Lombardo was directed to take a team of workers to clear out old equipment in the former children’s home (since razed). There, he found cabinets full of files that also led him to an index card with his name, birth date (July 29, 1940) and commitment date and number.

He argued with county officials about keeping the card, but he now had more information that also led to him to parts of the city where he said he could very well have run into his real mother without ever knowing it. He even took out a newspaper ad asking anyone who knew his mother or other relatives’ names he had uncovered to contact him directly at his phone numbers.

All of his sleuthing, however, never led to a living Mary O’Neil. She died in 1997 in a local group home, right around the time her son was promoted to Milwaukee County facilities and grounds supervisor. Jim held that position until his retirement in 2004.

An aunt eventually helped Lombardo locate his mother’s burial site in a crypt at Pinelawn Cemetery on Milwaukee’s far West Side.

“I felt very bad about that,” he said, “but at least I was able to find where she was buried.” He ordered a flower urn that sits below the crypt. It reads “Mary C. O’Neil Mother of James L. O’Neil.”

Jim visits his mother’s resting place annually each spring or early summer.

Quest for dignity

Though he did not readily equate it directly with his own life, Lombardo said he has been drawn over the years to the resting places of thousands of others – many orphans from the same county institutions — buried in various locations throughout the country grounds.

“I don’t know why, exactly, but it seemed like nothing was kept up – forgotten,” he said.

“I don’t know why, exactly, but it seemed like nothing was kept up – forgotten,” he said.

In particular, he saw from his vantage point as grounds supervisor the overgrown, neglected Potter’s Field where a sign explains that an estimated 4,000 of the 7,500 indigent children and adults are buried on county grounds from 1872 to 1974.

Figuring that cleaning up the field would not be met with support from his superiors, Lombardo deployed an off-the-books mission with a crew to clean up the field. It wasn’t a popular mission, Lombardo said, but he smiles at the fact that Milwaukee County has seen fit to keep up the maintenance he first forged during his tenure.

The field’s chain link fence now has a locked gate, a fact that disturbs Lombardo, who said the flat stones that mark the burials – many of which are several deep – lie undetected from afar an inch or two below the surface.

“I don’t know why they locked it,” he said. “It’s just wrong.”

What’s next?

Lombardo is somewhat of a grave-warrior pioneer. Others, including a local physician and scout, more recently have made it their mission to better recognize and dignify those who are buried in Asylum Cemetery north of Watertown Plank Road and others more anonymously buried in several areas under and near the Regional Medical Center.

This part of the story evolves; Tosa Connection will explore and present its findings in the Spring, 2019 issue.